On the morning of January 14, 2026, the employees of NAAREA arrived at work expecting salvation. After six months in judicial reorganization, the French nuclear startup had finally found a buyer. The Polish-Luxembourgish energy company Eneris was set to acquire them the very next day, preserving 108 of their 206 jobs. The nightmare, it seemed, was ending.

Then came the cold shower.

Hours before the scheduled court hearing, Eneris announced it was walking away. The company cited "the discovery, after the filing of its offer and at the hearing of the court, of legal, social and technological elements that had been concealed."

More damning still: Eneris declared that NAAREA was "in a technological impasse on its project of a fast neutron microreactor."

The accusation sent founder Jean-Luc Alexandre into a fury. "The real reason is that Eneris doesn't have the funds to carry out this operation," he stormed to reporters, insisting his buyer knew "nothing about nuclear."

His protests fell on deaf ears. Within five days, Eneris, having been forced by the court to complete the acquisition anyway, filed for bankruptcy of NAAREA itself, bringing a definitive end to one of France's most ambitious bets on next-generation nuclear technology.

How did a company backed by the French government, partnered with industrial giants like Dassault Systèmes and Orano, and celebrated as a flagship of the France 2030 innovation program, collapse so spectacularly?

The answer lies in a volatile mix of technological ambition, investor skittishness, government bureaucracy, and perhaps the fundamental impossibility of building a revolutionary nuclear reactor on a startup timeline.

The fallout from this nuclear failure has implications beyond one startup gone awry. As France has positioned itself as a global AI champion, one of its selling points has been its nuclear power base and its backing of innovative nuclear solutions such as SMRs. The nation received record investment last year from foreign investors for new data centers, but it's on the hook to deliver the power.

An inability to fulfill France's nuclear plans could short-circuit its AI ambitions as well.

The Engineer With a Vision

Jean-Luc Alexandre was not your typical startup founder. A graduate of CentraleSupélec, one of France's elite engineering schools, he had spent decades in heavy industry, including railways at Alstom, water treatment at Suez, where he rose to lead the company's global operations. He knew how to run massive infrastructure projects. What he didn't know, initially, was that he would spend the final chapter of his career chasing a dream born at a climate conference.

I reached out to Alexandre for comment this week, but he did not respond to requests for an interview.

The spark came at COP21 in Paris in 2015. Alexandre was working on sustainable development goals when a simple truth crystallized: every one of the 17 SDGs adopted by 193 countries depended on one thing. "The answer was energy, pure energy," he told me in a December 2023 interview. "This is the unique transmitter. So the lever of sustainable works is energy."

I spoke with Alexandre as part of a feature for Sifted in 2023 about France's ambitions to leverage its nuclear history to create an innovative nuclear ecosystem. You can read that story here.

But what kind of energy? Solar and wind were intermittent. Natural gas was still a fossil fuel. And conventional nuclear, while carbon-free, came with baggage: massive construction costs, water-cooling requirements, and the seemingly intractable problem of long-lived radioactive waste.

Alexandre saw a different path. During his years at Suez, he had become intimately familiar with waste-to-energy systems, the circular economy principle of turning one industry's garbage into another's fuel. What if the same logic could apply to nuclear? What if you could build a reactor that literally consumed nuclear waste as fuel?

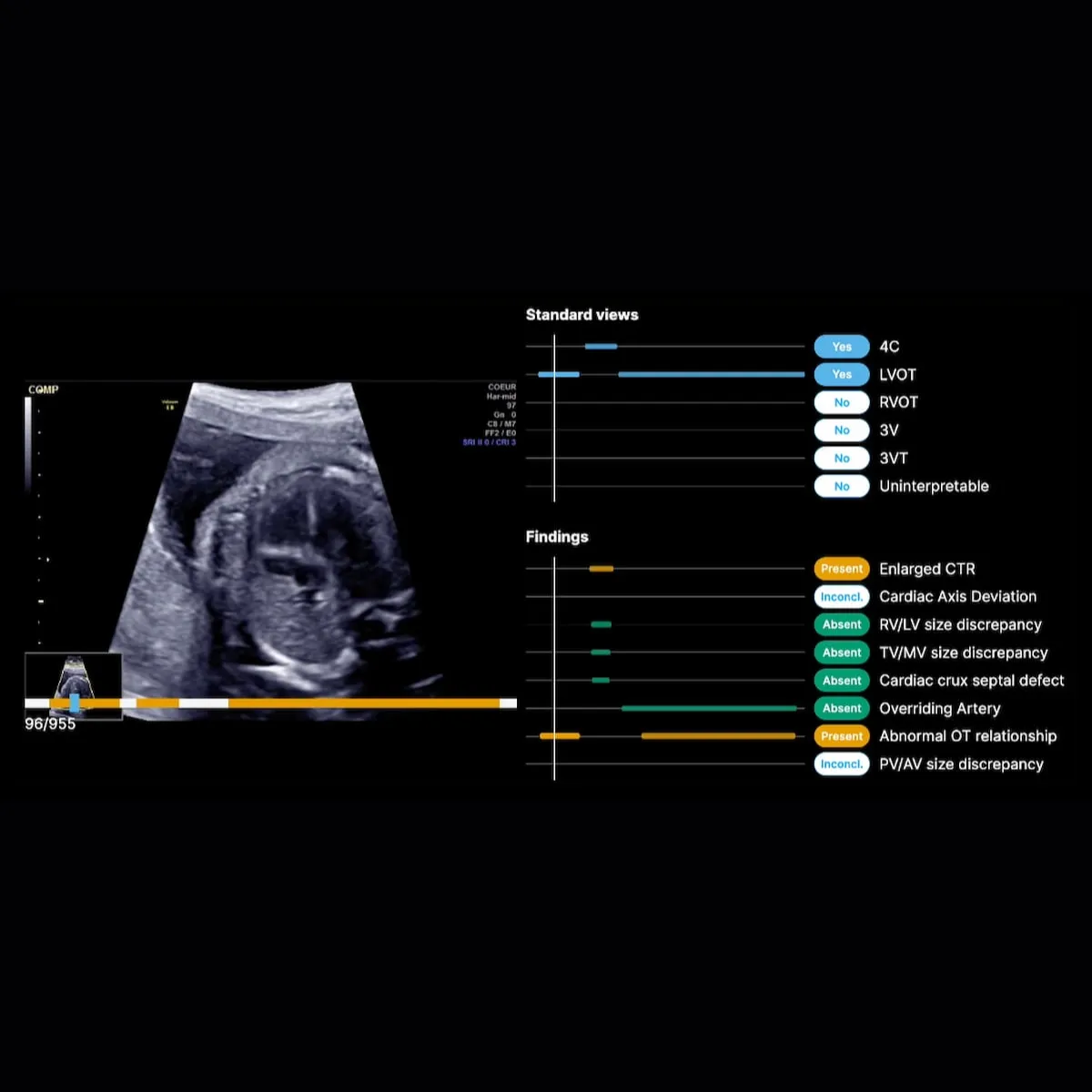

The technology existed, at least in theory. Molten salt reactors had been developed at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee during the 1950s and 1960s. By dissolving nuclear fuel directly into liquid salt, rather than using solid fuel rods cooled by water, these reactors offered inherent safety advantages. The physics of the system meant it would naturally slow down if it overheated, rather than risking a meltdown. Add fast neutrons to the mix, and you could theoretically "burn" the long-lived actinides that make conventional nuclear waste dangerous for hundreds of thousands of years.

France, crucially, was one of only two countries in the world (alongside Russia) that had built and operated fast-neutron reactors. The expertise existed. The academic research, conducted over nearly two decades at IJCLab under the supervision of the CNRS and Université Paris-Saclay, had laid the theoretical groundwork. All that was needed was someone bold enough to commercialize it.

In 2020, in the depths of the COVID pandemic, Alexandre founded NAAREA: an acronym for Nuclear Abundant Affordable Resourceful Energy for All. The name captured his ambition: not just another nuclear company, but a democratization of atomic energy itself.

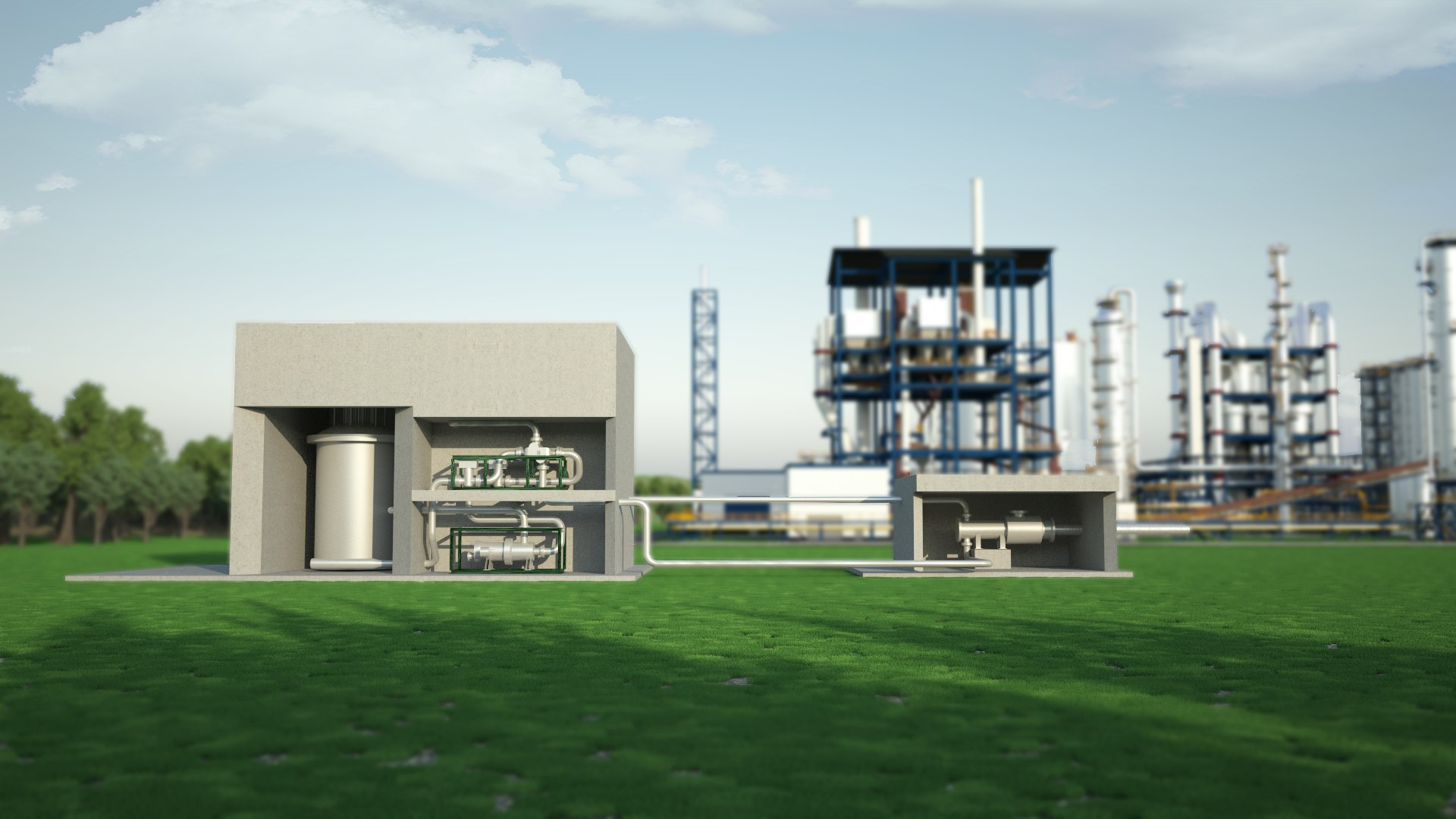

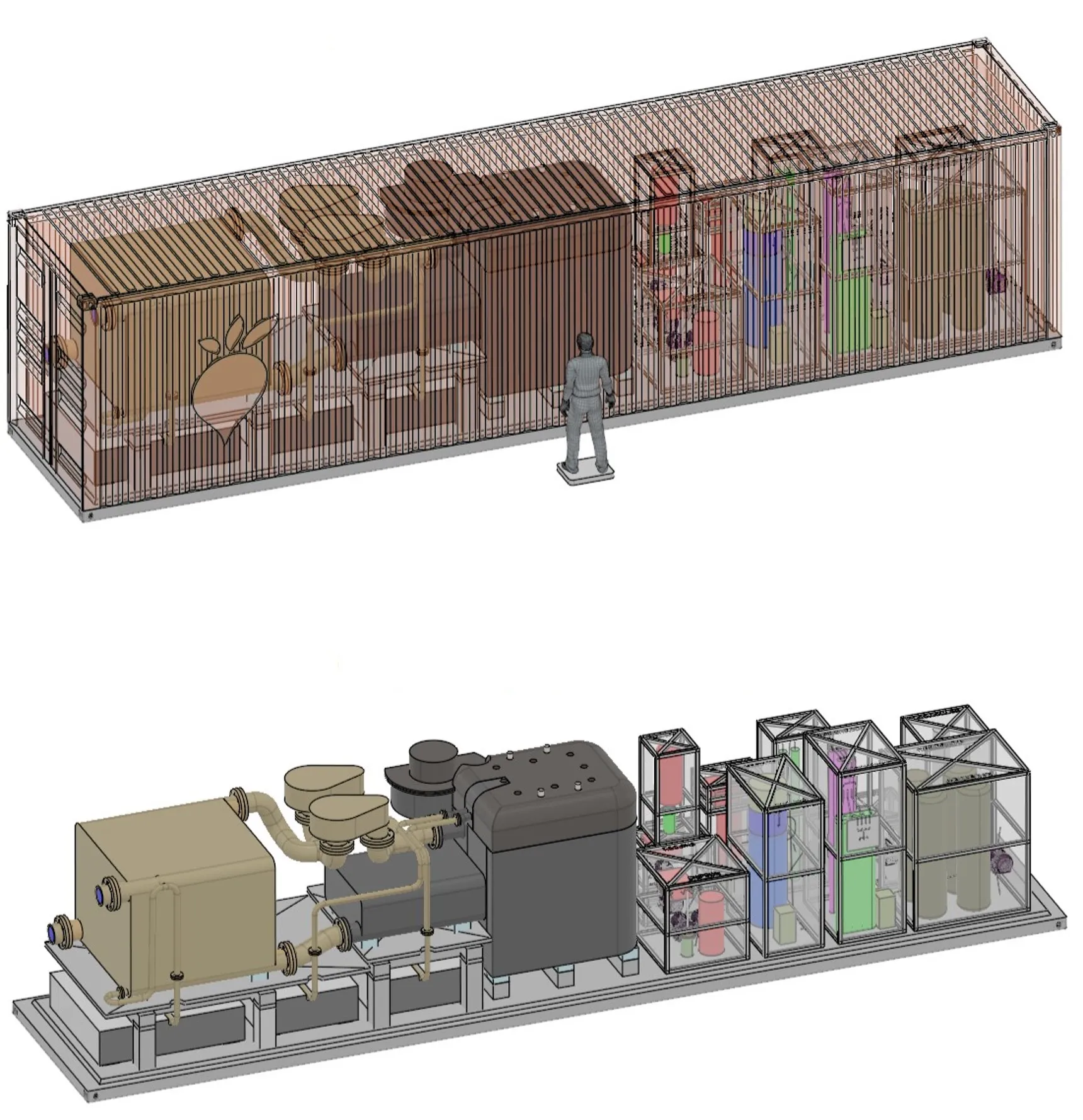

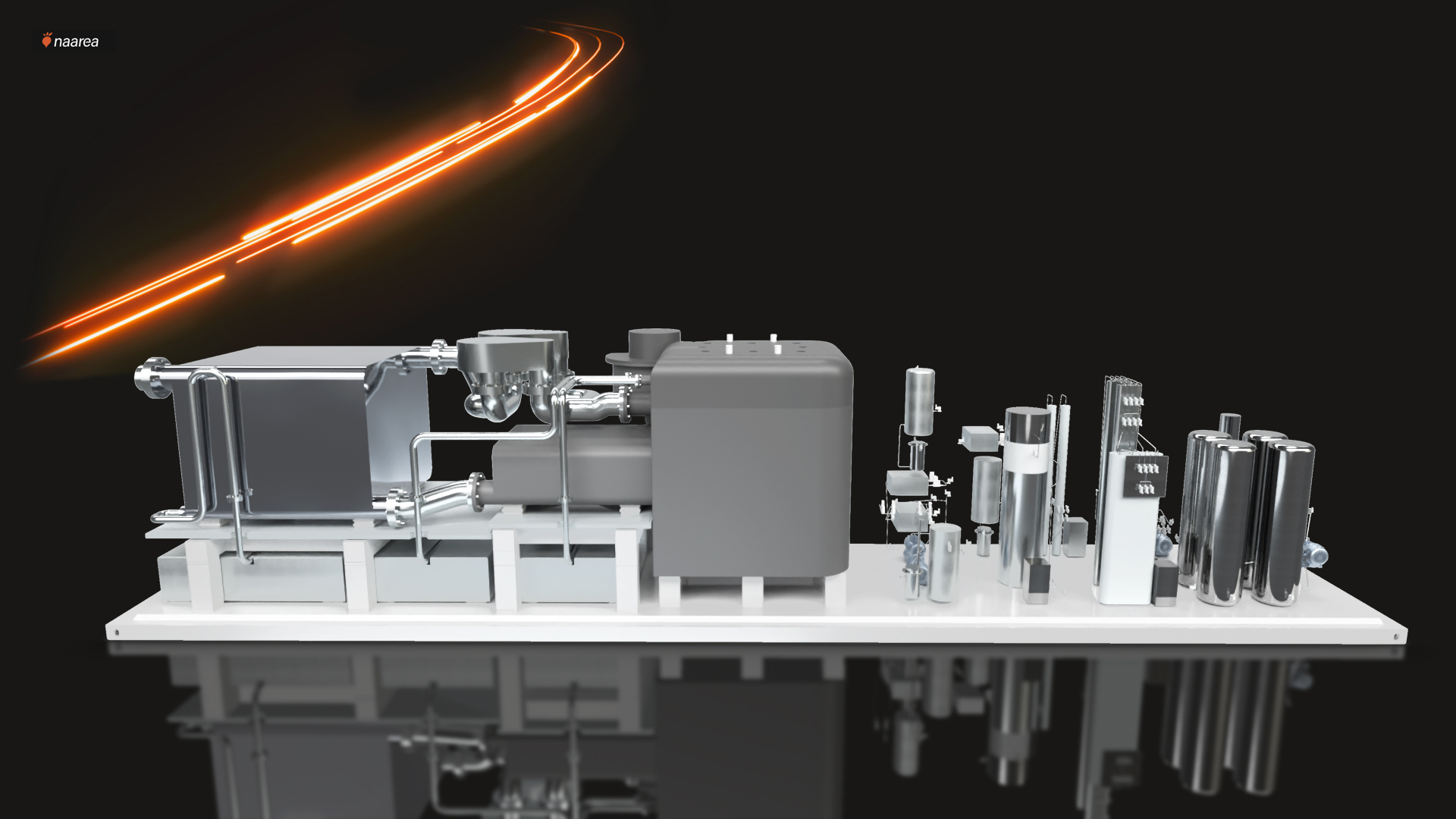

The XAMR: A Reactor in a Shipping Container

The technology NAAREA proposed was audacious. The XAMR (eXtrasmall Advanced Modular Reactor) would pack a fourth-generation molten salt reactor into a package the size of a 40-foot shipping container. Operating at 700°C with no water cooling required, it would produce 40 megawatts of electricity and 80 megawatts of thermal heat. That's enough to power a medium-sized industrial facility while simultaneously providing the high-temperature heat needed to decarbonize manufacturing processes.

"80% of the energy consumed by industry is for heating," Alexandre explained to me. "Industrial processes need heat. Today, a lot of people are saying, 'Let's go for electrifying everything.' That's not correct."

His pitch was elegant: deliver carbon-free energy directly to factories, in the desert, in the mountains, anywhere an industrial customer needed it, without building new transmission lines or fighting for grid capacity.

The business model was equally radical. Unlike conventional nuclear vendors who sell reactors, NAAREA would sell energy. The company would design, manufacture, deploy, and operate the reactors itself. The customer would simply pay for the kilowatt-hours consumed. It was the utility model applied to distributed nuclear power, turning a capital equipment sale into a recurring services business.

On paper, it was brilliant. In practice, it required solving problems that had stymied engineers for seventy years.

The Government Bet

The political sea change that made NAAREA possible can be traced to a single speech.

On February 10, 2022, at a General Electric turbine factory in Belfort, President Emmanuel Macron announced the most ambitious French nuclear program in decades. After years of political hedging, Macron made an abrupt U-turn. His government had previously committed to reducing nuclear power's share of electricity to 50%. Now, he announced that France would build six new EPR2 reactors, with options for eight more as part of the €58 billion France 2030 program announced the previous year as part of his post-COVID rebuilding program.

The new nuclear program would extend the life of existing plants beyond 50 years. Crucially for startups like NAAREA, it would invest €1 billion specifically in innovative small modular reactors and advanced nuclear technologies. "What we need is a nuclear renaissance," Macron declared. The speech marked France's definitive break from the post-Fukushima consensus that had seen Germany shutter its reactors and much of Europe turn away from atomic energy.

NAAREA, alongside the UK-Italian startup Newcleo, became one of the first two winners of the program's nuclear innovation call. The direct funding was a modest €10 million. But the symbolic value was immense.

"It means that the government gives you a stamp on the credibility of your project," Alexandre explained. For private investors wary of nuclear's regulatory complexity, government endorsement from a country with France's nuclear heritage provided crucial reassurance.

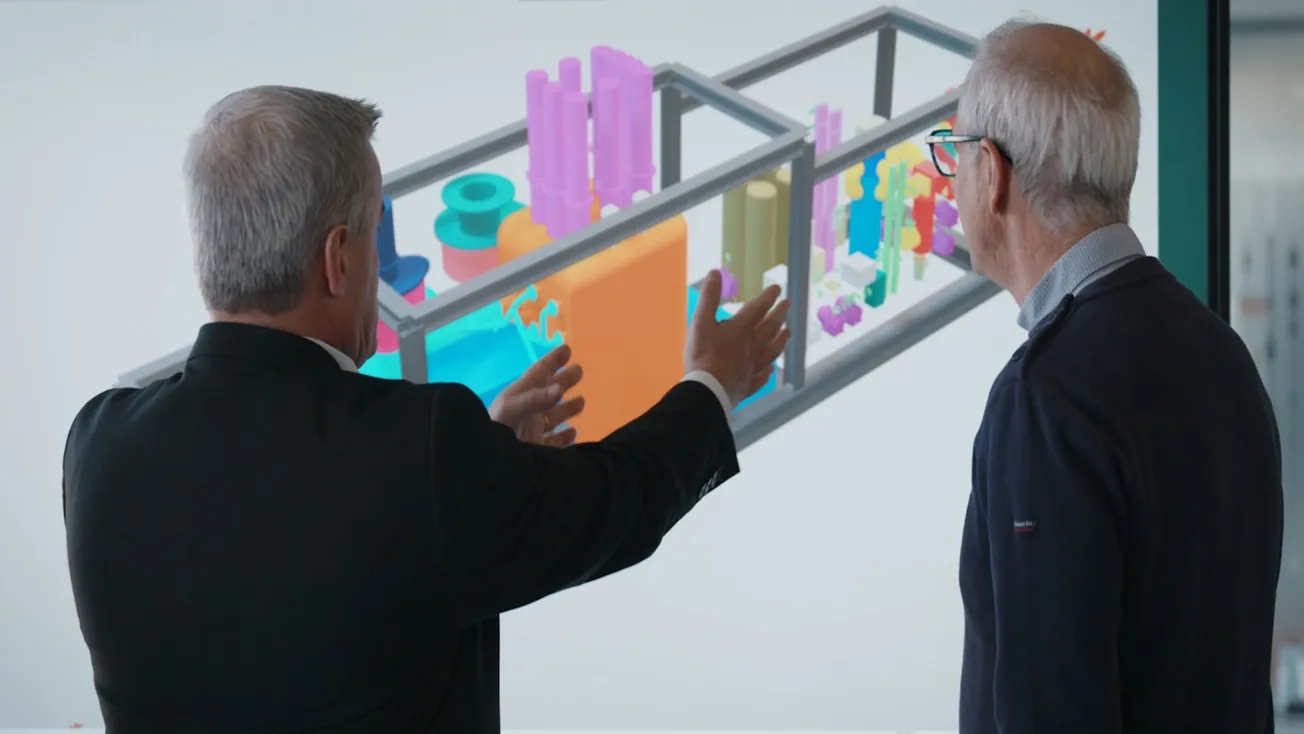

By 2023, NAAREA had raised approximately €50 million, primarily from Eren Groupe, an energy investment company founded by former EDF Renewables executives. The company had grown to roughly 90 employees and was making technical progress on its digital twin, a sophisticated computer simulation of the reactor developed in partnership with Dassault Systèmes.

The selection opened doors to partnerships with CEA (France's atomic energy commission), formalized research collaborations with CNRS and Université Paris-Saclay, and culminated in June 2024 with the creation of the Innovation Molten Salt Lab, a joint laboratory explicitly designed to make France "the European leader in the field of molten salts research and development."

NAAREA was flying high.

The company expanded rapidly, reaching 206 employees by late 2025. It signed cooperation agreements with Assystem, Orano, and other nuclear industry heavyweights. In September 2024, working with the European Commission's Joint Research Centre, NAAREA announced it had developed reproducible methods for synthesizing plutonium and uranium chloride fuel salt, a critical milestone that no one else in the West had achieved.

The future, it seemed, was bright. In November 2023, NAAREA announced plans to raise an ambitious €150 million Series A with Rothschild & Co. advising. The funds would accelerate development toward a prototype by 2027 and commercial production by 2030.

Then the music stopped.

The NuScale Effect

To understand what went wrong, one must first look across the Atlantic.

In November 2023, the same month NAAREA announced its fundraising goal, NuScale Power, the most advanced small modular reactor developer in the United States, cancelled its flagship project in Idaho. The company that had become the first ever to receive design approval from the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission for a small modular reactor had failed to line up enough customers to make its economics work.

The news sent shockwaves through the nuclear investment community. If NuScale, with its regulatory approvals and utility partnerships, couldn't make SMR economics pencil out, what chance did earlier-stage companies have?

For NAAREA, the timing was catastrophic. Venture capitalists who had been circling the nuclear space suddenly remembered why they traditionally avoided it: decade-long development timelines, regulatory uncertainty, and capital requirements that dwarfed typical tech investments. The €150 million Series A never materialized.

But there were other issues closer to home.

While Macron was re-elected in 2022, he was politically weakened when his party did not win a clear majority in the National Assembly. Stuck in a political morass, he made a controversial decision to dissolve the legislature in the summer of 2024, only to see his support further erode and cycle through a series of prime ministers who struggled to stitch together support for his programs.

By October 2024, the increasingly fractured French Assembly was voicing growing doubts about the nuclear program.

In a detailed budgetary review presented to the National Assembly's Committee on Sustainable Development, rapporteure Constance de Pélichy delivered a sobering assessment of the country's SMR ambitions.

While praising France 2030's €1.2 billion nuclear investment, she questioned whether the eleven startup laureates of the "Innovative Nuclear Reactors" competition, including NAAREA among them, could actually deliver on their promises.

"The arrival of new private actors raises questions about their capacity to ensure the safety of their installations, their capacity to respond in the event of a nuclear accident, their financial solidity given the fragility of the economic model, and their responsibility for managing nuclear waste," she warned.

The report pointed out that EDF's own SMR project, Nuward, had been suspended just months earlier after receiving €300 million in state commitments, a stark illustration of how even industry giants were struggling with the technology. The CEA had told legislators that the France 2030 funding envelope was "only dimensioned to make one French champion emerge" in SMRs and was "too weak to financially accompany two projects to the end."

For NAAREA, already hemorrhaging cash and struggling to close its fundraising round, the message from Paris was clear: the cavalry was not coming.

NAAREA's problem went back to the way the original €1 billion for France 2030's "Innovative Nuclear Reactors" program was structured: a three-phase competition designed to winnow promising concepts into commercial reality:

- Phase I would fund conceptual development and feasibility studies.

- Phase II would support detailed engineering and prototype preparation.

- Phase III would finance actual demonstration reactors.

NAAREA had been part of Phase I. The implicit promise was clear: perform well in Phase I, and substantially larger government checks would follow.

But the gap between presidential ambition and bureaucratic execution proved fatal for NAAREA. While Macron spoke of urgency and renaissance back in 2022, the General Secretariat for Investment (SGPI)—the body responsible for actually disbursing France 2030 funds—moved at its own deliberate pace. Phase II of the nuclear innovation program, which would have provided the next tranche of funding for NAAREA and the credibility signal that private investors were waiting for, remained perpetually imminent but never arrived.

"We are still waiting for phase II; the SGPI is slow," an industry expert told Le Figaro after NAAREA's collapse. "The President of the Republic has nevertheless asked in March 2025 for an acceleration of decision-making."

The irony was brutal: a program designed to help startups move faster than incumbent nuclear giants had itself become a bottleneck, its timelines better suited to state-owned enterprises with decades of runway than venture-backed companies burning through cash. By the time NAAREA entered judicial reorganization, the Phase II funding that might have saved it remained stuck somewhere in the machinery of the French government.

The Rise & Fall of NAAREA

A timeline of France's most ambitious nuclear startup — from revolutionary promise to spectacular collapse in just five years

NAAREA is Born

Jean-Luc Alexandre, a former Airbus executive, founds NAAREA with a bold vision: build compact molten salt reactors that can be transported by truck and deployed anywhere. The XAMR (eXtrasmall Advanced Modular Reactor) promises to revolutionize nuclear energy.

FoundationMacron's Nuclear Renaissance

President Emmanuel Macron delivers his historic Belfort speech, announcing plans for 6-14 new EPR reactors and €1 billion for innovative nuclear research through the France 2030 program. NAAREA appears perfectly positioned to benefit.

Government SupportInvestor Frenzy

Riding the wave of nuclear enthusiasm, NAAREA secures major funding rounds. The startup attracts prominent investors including Jacques Veyrat's Impala group and the Bettencourt-Meyers family. Total investment will eventually reach €90 million.

FundingFrance 2030 Phase I Victory

NAAREA is selected among the winners of France 2030's first phase for innovative nuclear reactors. The company receives initial government backing and validation of its technology approach. The future looks bright.

MilestoneThe NuScale Shockwave

America's most advanced SMR project collapses when NuScale abandons its Idaho plant due to soaring costs. The failure sends shockwaves through global nuclear investment. Private capital for advanced reactors begins drying up worldwide.

Industry CrisisParliament Sounds the Alarm

The French National Assembly releases a damning report on France 2030's nuclear research funding. It reveals that AMR startups are trapped in a "valley of death" — private investors won't commit without government Phase II funding, which remains stuck in bureaucratic limbo.

Warning SignsToo Little, Too Late

President Macron orders the SGPI (government investment secretariat) to accelerate decision-making. But the bureaucracy has already consumed precious time. NAAREA's cash reserves are running dangerously low.

Government DelayFiling for Protection

NAAREA files for judicial reorganization (redressement judiciaire) at the Commercial Court of Nanterre. CEO Alexandre blames investor hesitancy tied to delays in France 2030's Phase II funding. The clock starts ticking.

Bankruptcy FilingThe Eneris Gambit

Polish energy group Eneris emerges as potential savior, offering to acquire NAAREA. But the bid comes with a devastating assessment: NAAREA's technology has reached an "impasse" and would require a complete restart under new leadership.

Acquisition AttemptThe Final Verdict

The Commercial Court of Nanterre rejects the Eneris bid, citing the company's failure to obtain ASN (nuclear safety authority) approval and lack of credible technical pathway. NAAREA is ordered into liquidation. The dream is over.

Liquidation"Le temps du nucléaire est long, mais celui des start-up l'est beaucoup moins."

(The time of nuclear power is long, but that of startups is much less.)

— Le Figaro, January 2026

"Investors were waiting for the launch of phase II of France 2030," Alexandre would later explain, referring to the next tranche of government funding that would further de-risk the technology. But phase II never came.

The General Secretariat for Investment (SGPI), the government body responsible for France 2030 implementation, moved at bureaucratic speed while NAAREA's cash runway evaporated.

The Political Climate That Shifted Too Late

The bitter irony of NAAREA's collapse is that it occurred precisely as the political climate for nuclear had become more favorable than at any point in a generation.

When Alexandre first conceived of the company in 2015, France was in the process of legislating a reduction in nuclear's share of electricity generation from 75% to 50%. Germany had committed to a complete nuclear phase-out. The European Union's taxonomy of sustainable investments explicitly excluded nuclear. Public opinion, shaped by memories of Fukushima, remained deeply skeptical.

By 2025, everything had changed. Russia's invasion of Ukraine had exposed Europe's energy vulnerability. Germany's electricity prices had soared after shutting down its last reactors. The EU had reversed course and included nuclear in its sustainable taxonomy. President Macron had made nuclear innovation a centerpiece of French industrial policy. At COP28 in December 2023, more than 20 countries pledged to triple global nuclear capacity by 2050.

But political support doesn't write checks. And the fundamental challenge facing NAAREA remained unchanged: Building technology that had never been commercially demonstrated, on a timeline that would satisfy venture capital return expectations, was proving a tough sell.

The math was brutal. To go from research to commercial deployment, NAAREA needed at least €200 million, possibly more. Prototype development alone would cost €20-50 million. Regulatory licensing in an evolving framework: another €10-30 million. Industrial-scale fuel production, supply chain development, test operations, and manufacturing scale-up each category demanded tens of millions more.

The €90 million raised for NAAREA was enough to build a team, conduct research, and create compelling digital simulations.

It was not enough to actually build a reactor.

The Final Act

On September 3, 2025, NAAREA filed for judicial reorganization in the Nanterre commercial court. The company had accumulated approximately €15 million in debt and could no longer make payroll. The judicial administrators launched an auction process, seeking a buyer willing to take on the company's obligations.

Only one serious bidder emerged: Eneris, a Polish-Luxembourgish energy company specializing in waste-to-energy systems. The companies had a history. Eneris had considered investing in NAAREA years earlier before backing out. Now, founder Artur Dela saw an opportunity to acquire advanced nuclear technology at a discount.

Through the fall of 2025, negotiations proceeded. By December, a deal was taking shape: Eneris would acquire NAAREA, retain 108 employees, and continue development of the XAMR technology. The court hearing to formalize the acquisition was scheduled for January 15, 2026.

What happened in those final weeks remains disputed.

Eneris claims it discovered, through due diligence, that NAAREA had concealed fundamental legal, social, and most critically, technological problems. Eneris concluded that the molten salt fast-neutron reactor design had reached a dead end, with "absence of any possible sustainability" for commercialization in the 2030s as NAAREA had promised.

Alexandre vehemently disputes this characterization, insisting the technology was viable and that Eneris simply lacked the funds to complete the acquisition.

The court's response to Eneris's withdrawal was extraordinary.

Ruling that the company had not followed proper procedures in attempting to back out, the judge ordered Eneris to complete the acquisition anyway. It was a pyrrhic victory. Five days later, Eneris filed for bankruptcy of the newly-acquired NAAREA subsidiary, bringing the saga to its inevitable conclusion.

What Remains

In the weeks following the bankruptcy filing, an unexpected silver lining emerged. Most of NAAREA's 206 former employees found new positions quickly, their skills in nuclear engineering, molten salt chemistry, and reactor physics in high demand across France's expanding nuclear sector. The expertise built at NAAREA dispersed into the broader French nuclear ecosystem—EDF, Framatome, and the very startups that will now attempt to carry forward the dream of advanced reactor technology.

The intellectual property, the research partnerships, and the laboratory work on fuel synthesis, none of this has been entirely lost. It will be sold to creditors, absorbed by other organizations, or continue through academic channels at institutions like Université Paris-Saclay. The knowledge generated by NAAREA's €90 million bet may yet contribute to a future where molten salt reactors finally achieve commercial viability.

But for France's nuclear innovation strategy, NAAREA's collapse raises uncomfortable questions.

Was the France 2030 program's €10 million commitment realistic relative to the capital requirements? Did government bureaucracy, in delaying phase II funding, effectively starve a promising venture? Can the traditional venture capital model ever work for technologies requiring decade-long development timelines?

Perhaps.

But the employees who lost their jobs, the investors who lost their capital, and the founder who lost his dream might be forgiven for questioning whether the mechanism worked as intended.

As France continues its nuclear renaissance, including building new EPR reactors, investing in other small modular reactor designs, and racing to maintain its position as a global nuclear leader, the wreckage of NAAREA serves as a cautionary tale. Revolutionary technology, government support, and private capital are necessary conditions for deep-tech innovation. They are not, as Jean-Luc Alexandre learned in the cruelest possible way, sufficient ones.

The molten salt reactor that was supposed to fit in a shipping container and solve industrial decarbonization now exists only in simulations and patent filings. The vision of nuclear energy abundant, affordable, and available for all remains, for now, exactly that: a vision.

Whether someone else will pick up where NAAREA left off with better timing, deeper pockets, or simply more luck remains to be seen. The physics hasn't changed. The climate emergency hasn't abated. And somewhere, perhaps, another engineer is looking at the sustainable development goals and asking the same question Alexandre asked a decade ago: How do we deliver carbon-free energy to the places that need it most?

The answer, it turns out, is still under construction.