Seven years ago, Sevan Marian and Alexandre Berriche each scraped together €2,500, pocket change by startup standards, and launched Fleet from a Paris apartment.

They had no venture capital, no debt facilities, no safety net. What they had was a simple bet: that mid-sized companies were tired of buying laptops outright and dealing with the headaches that followed.

On Monday, Fleet announces it has reached a €100 million valuation and is opening its capital to outside investors for the first time. ISAI Expansion, the private equity arm of one of France's pioneering tech investment firms, is taking a minority stake in a deal that provides liquidity to the founders and, critically, to employees who bet on the company when no one else would.

"We invested two and a half thousand euros each six years ago, and it became 100 million," Marian said in an interview, still sounding slightly amazed. "Which is crazy."

The deal marks a turning point for a company that has become something of a cult hero in French tech circles, proof that you don't need to play the venture capital game to build something significant.

But it also raises a question that Marian and Berriche have been wrestling with for months: after building an identity around being bootstrapped, why change course now?

The Anti-VC Playbook

Fleet's origin story reads like a deliberate rejection of the startup orthodoxy that dominated the late 2010s. While their peers were raising seed rounds and chasing growth at any cost, Marian and Berriche were doing something unfashionable: making money.

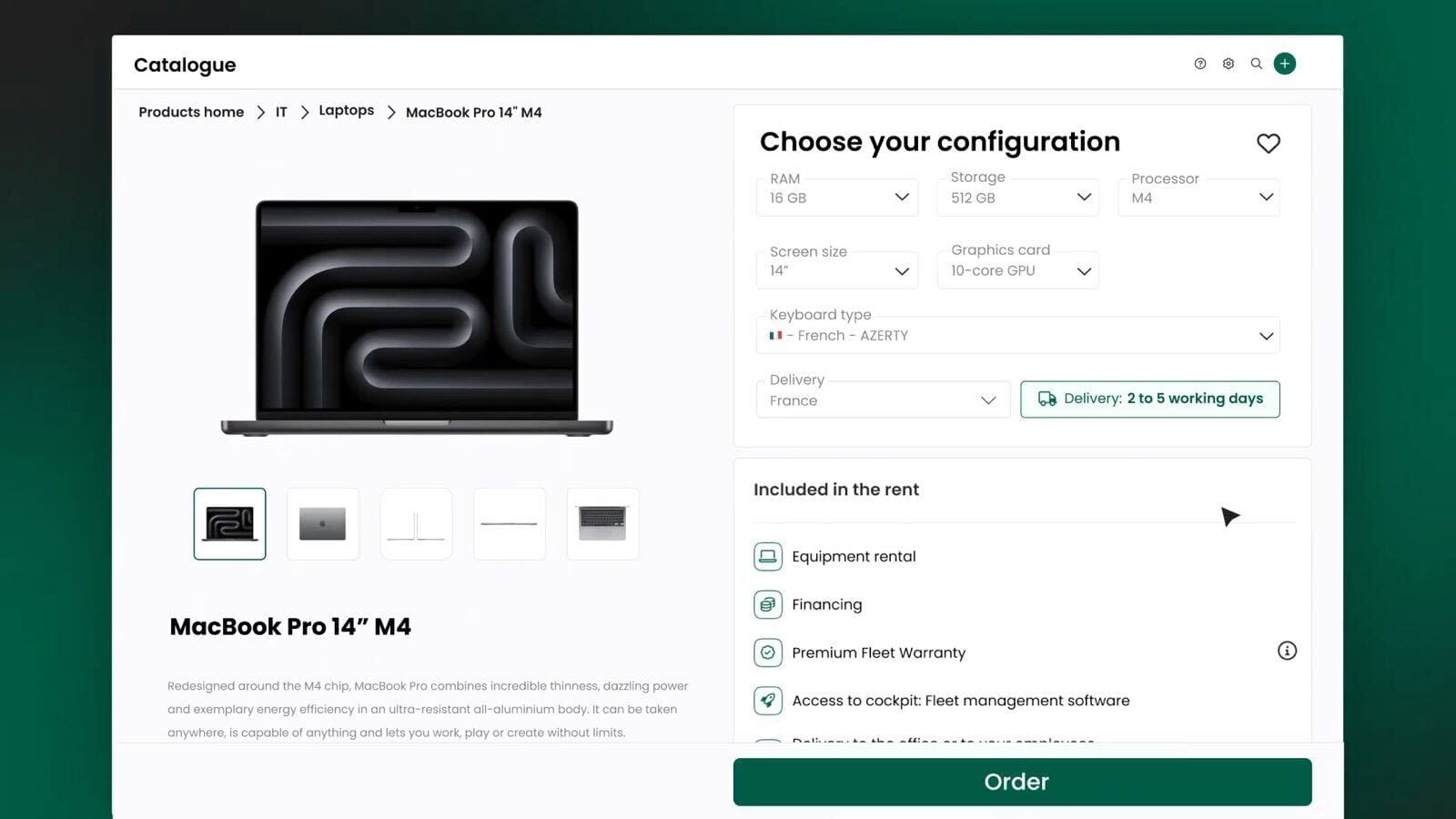

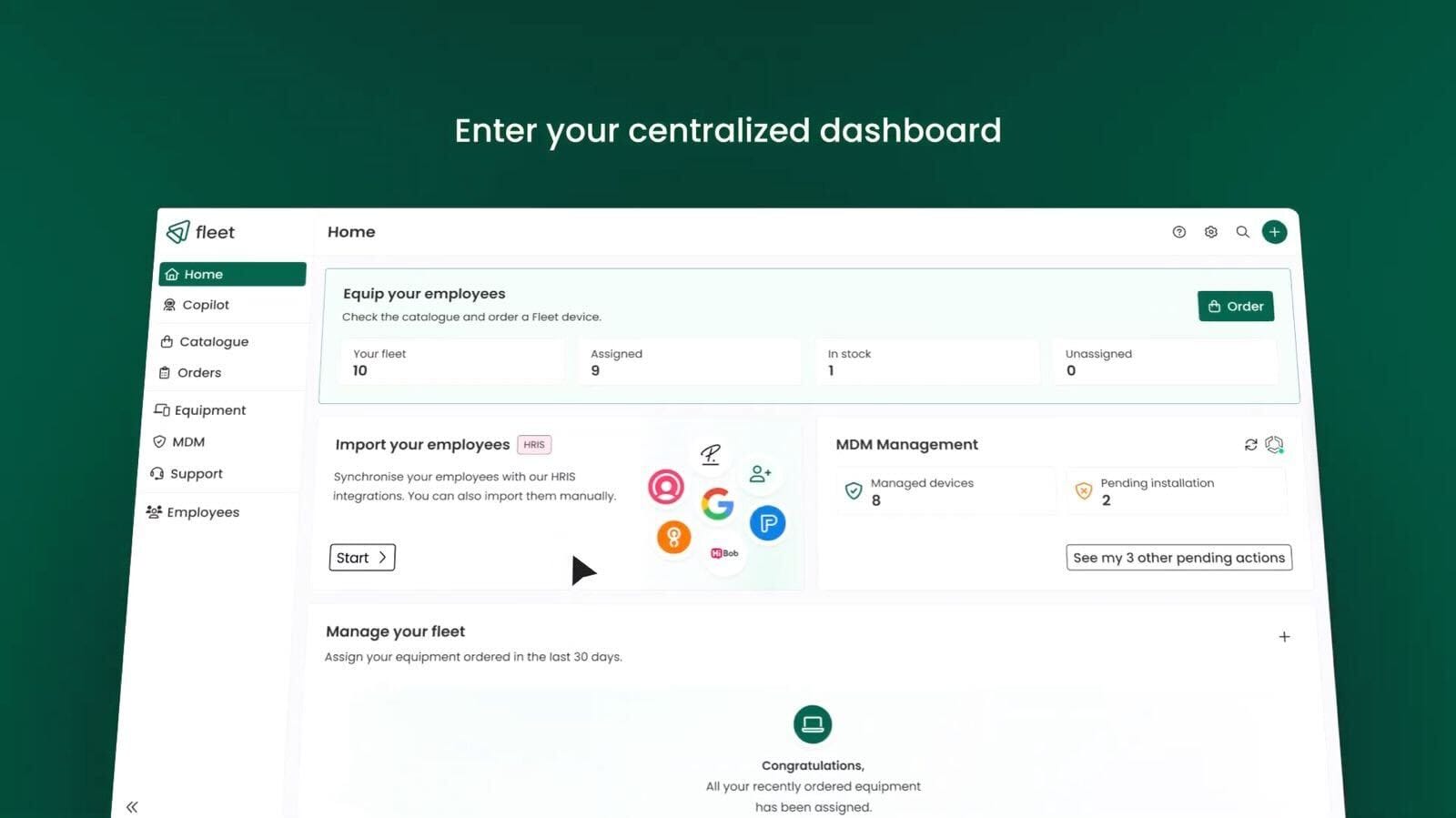

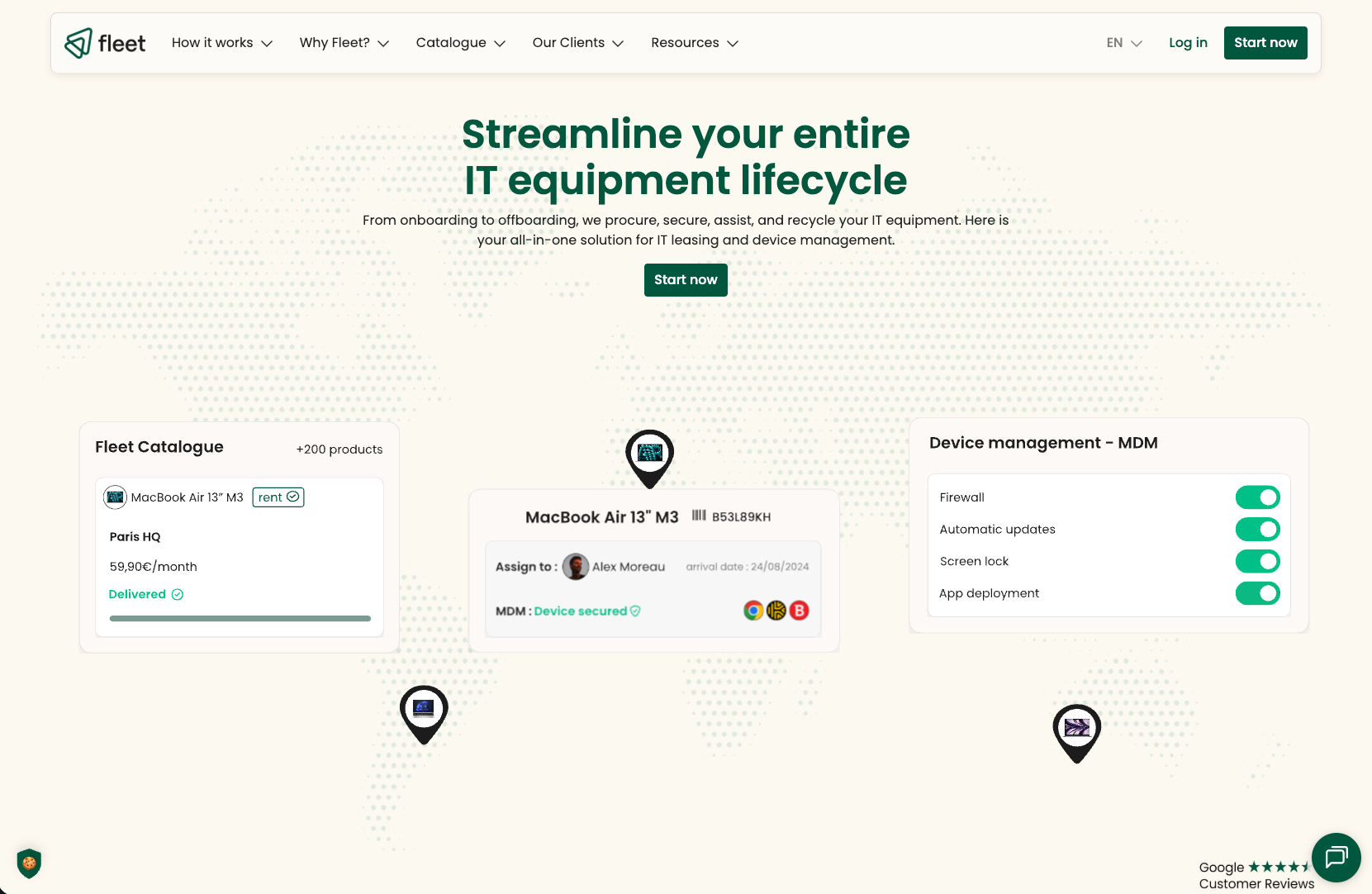

The business model was deceptively simple. Companies with five to 500 employees could lease laptops, tablets, phones, and even office furniture through Fleet's platform, converting capital expenditures into predictable monthly payments. Fleet handled procurement, device management, security, maintenance, and end-of-life recycling. The customer got a single platform called "Cockpit" and never thought about IT equipment again.

"After six months, we sat down together and said, okay, we have a lot of cash in the bank. The more we grow, the more we accumulate cash, because we have almost negative working capital," Marian recalled. "Does it make sense to raise money? Or can we grow just with our own cash?"

They chose the latter. The decision forced architectural choices that would prove prescient. Fleet operates a drop-shipping model, avoiding inventory costs. Rather than financing customer leases from its own balance sheet, the company integrated directly with French banks' APIs, essentially acting as a broker. Suppliers got paid late; customers paid monthly upfront. Cash flowed in faster than it flowed out.

The result was a company that grew 60 percent in 2024 and then 92 percent in 2025, reaching more than €30 million in annualized revenue while remaining profitable with just 45 employees. Two-thirds of that revenue now comes from outside France, with operations spanning Spain, Germany, the UK, the Netherlands, Italy, and a fast-growing American business launched nine months ago that's already generating €6 million annually.

"We've made a longer journey, a long pass," Marian acknowledged. "But today we have a very solid foundation."

The Butterfly Effect

If Fleet had followed the traditional path, it might have raised a seed round in 2019, a Series A in 2021 at an inflated valuation, and then faced the brutal reckoning that hit European tech in 2023. Instead, the company sailed through the venture capital winter unscathed.

"We went through this VC crisis, especially in Europe and in France, in 2023," Marian said. "What was maybe at the beginning not a weakness, but something harder for us, became a strength."

The founders have started calling bootstrapped success stories "butterflies": companies that grow like caterpillars before transforming into something bigger. It's a deliberate counter to the unicorn mythology that has dominated tech culture.

"We don't really make the headlines when we don't raise money," Marian said. "We talk about unicorns. I think we should celebrate this more."

Why Now?

So why, after seven years of principled independence, open the door to outside capital?

The answer involves both personal and strategic calculations.

In January 2025, Berriche stepped back from the CEO role to become Executive Chairman, while Marian took sole command. Berriche had developed a parallel career as one of Europe's most prolific angel investors. He's a scout for Sequoia Capital and was ranked the number-one investor on Sifted's 2025 AI 100 list, with a portfolio that includes a stake in Lovable that has returned more than 100 times his investment.

"Since Alex is now more or less part-time and not fully invested in the company, maybe we should make a difference in the cap table between us," Marian explained. "That was the first reason."

The second was more philosophical. After seven years, the founders wanted external validation of what they'd built, a real number backed by real money, not a theoretical valuation from a previous funding round.

"It's a real €100 million valuation, because it's only secondary," Marian emphasized. "There is no cash in the company. It's only cash out."

The third reason may be the most significant. Fleet had given stock options to early employees, but stock options in a bootstrapped company are abstract promises of future value with no obvious path to liquidity. The venture capital collapse of recent years has left many startup employees at other companies holding worthless paper, poisoning the well for equity compensation.

"The image of stock options in the ecosystem has been very bad lately," Marian said. "We wanted to give liquidity and to tell the story that many people at our company became rich thanks to us."

Employees are receiving full cash-outs on their options, totaling €2-3 million across the team.

Berniche and Marian will also completely cash out, but...they are also reinvesting and will remain majority shareholders. Which means that – yes – between the two of them, the are putting €50 million back into the company.

"The PE fund is a minority and we stay in command," he said.

The Road to €100 Million in Revenue

The ISAI investment isn't about survival. Fleet doesn't need the money to operate. It's about acceleration. The company aims to grow from €30 million to €100 million in annual revenue within four years, a trajectory that will require executing on multiple fronts simultaneously.

The immediate priority is geographic expansion. The American market, operated entirely from a Barcelona sales hub with staff working shifted hours, is Fleet's fastest-growing region. Marian plans to establish a proper US presence with local hires.

But the bigger strategic bet involves transforming Fleet from a device management company into what Marian calls an "AI MSP"—an artificial intelligence-powered managed service provider. Today, Fleet excels at hardware lifecycle management and automated employee onboarding and offboarding. Tomorrow, it wants to handle the entire IT stack: software issues, printer problems, access management, and the daily friction that bogs down small and medium businesses without dedicated IT departments.

"This market is very old school," Marian said of traditional managed service providers. "Small players, not digitalized, that come in the office to help you. We want to, thanks to AI, disrupt this market and create this full-stack solution."

The timing, he argues, is finally right. Remote and hybrid work have created distributed teams that local IT providers can't serve. Cloud computing means most infrastructure can be managed remotely. And AI is making it possible to automate the kind of support that previously required human technicians.

Remaining in Command

Despite taking outside investment, Marian and Berriche have structured the deal to maintain control. ISAI Expansion holds a minority stake with board representation and veto rights, but the founders remain majority shareholders.

"We stay in command," Marian said. "Alex, both of us are majority shareholders if we sum up our shares."

It's a conscious rejection of the typical private equity playbook, where financial sponsors often take controlling positions and install their own management. ISAI Expansion, whose portfolio includes French success stories like Theodo and aDvens, has a track record of backing profitable, founder-led companies through growth phases without seizing the wheel.

For Marian, the deal represents something like having it both ways: the validation and liquidity of outside investment without sacrificing the independence that made Fleet's journey possible.

"You can go big, grow big, be very ambitious, scale fast, without raising money if you have the right business model and if it's the right choice for you," he said. "It's not automatic to raise money. You have to ask yourself as a founder: Do I want that? Does my business require this?"

Seven years and 20,000 times his initial investment later, Marian finally has his answer.