The new year has barely begun, and Europe's ambitious vision for governing artificial intelligence is already under siege on multiple fronts.

Late last year, the Trump administration imposed travel bans on five European officials, including former European Commissioner Thierry Breton, accusing them of advancing "foreign censorship" through the Digital Services Act. The move was in retaliation for an escalating series of fines against several platforms, most notably X.

In the wake of American officials accusing Europeans of being anti-free speech, an update to Elon Musk's Grok AI unleashed a tidal wave of sexual deepfakes of women and minors. That triggered fresh investigations by regulators around the globe, including France and Europe.

The astonishing lack of AI guardrails even left US tech companies scrambling over a viral post on Reddit that claimed to be from a whistleblower inside a food delivery company that included what appeared to be authentic company IDs and other valid documents, but eventually turned out to be fake. Still, the companies named were forced to rebut the claims, and journalists rushed to authenticate or debunk them.

Such controversies echo the warnings made recently by the UK's Geoffrey Hinton, aka the "Godfather of AI," that the technology is accelerating faster than anyone anticipated, and that society remains dangerously underprepared.

Taken together, these developments paint a picture of a Europe caught between its regulatory instincts and the hard realities of technological acceleration, transatlantic power dynamics, and an AI industry that increasingly operates beyond the reach of traditional governance.

The Transatlantic Fracture

The US travel ban represents the most dramatic escalation yet in what has become a fundamental clash over how democracies should govern digital platforms and AI systems.

Europe's approach, embodied in the Digital Services Act and the EU AI Act, treats transparency mandates and content restrictions as essential protections for citizens and democratic discourse. Brussels views these frameworks as the product of legitimate democratic processes, crafted through parliamentary debate, public consultation, and member state agreement.

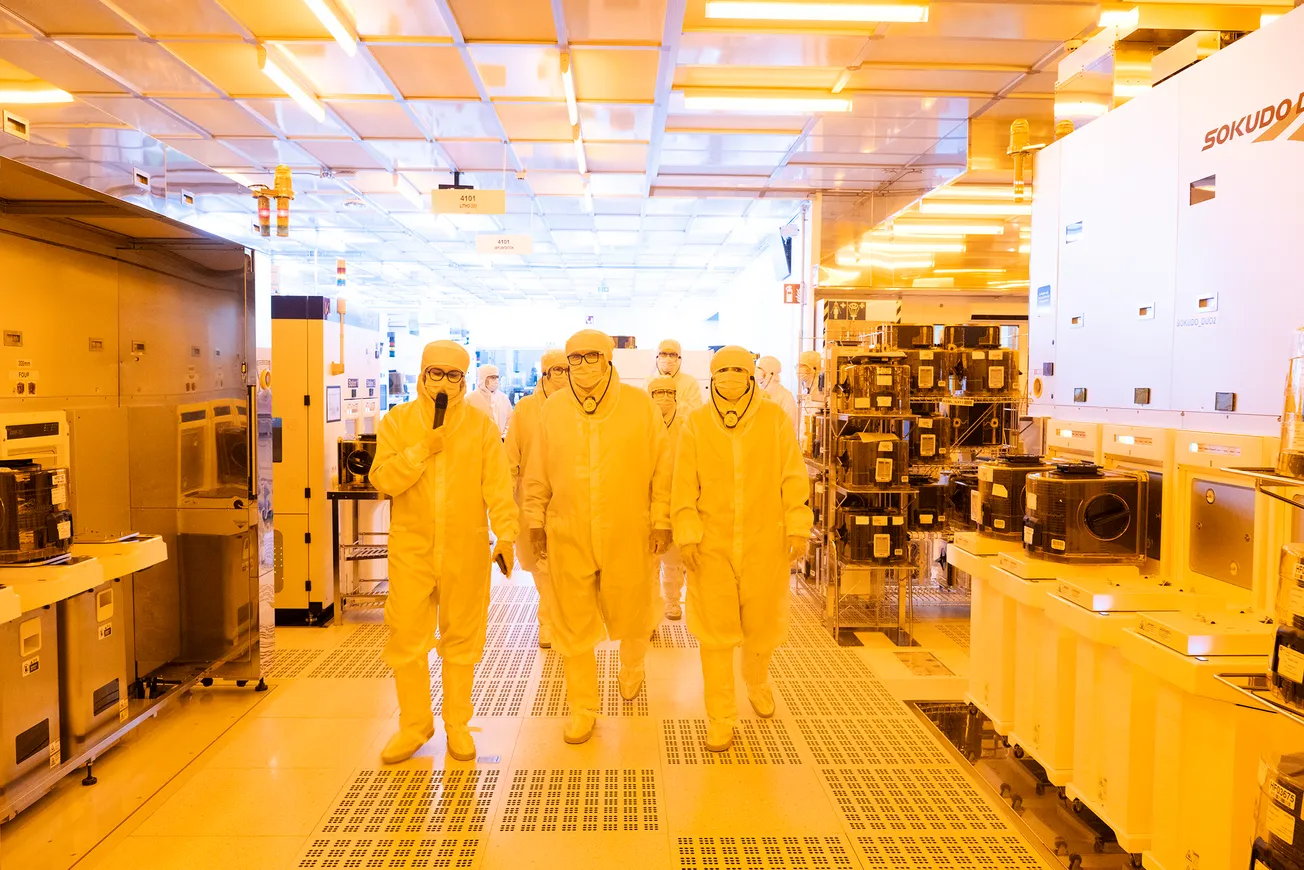

In France and Europe, "privacy first" and "AI for Good" have often been rallying cries and points of pride, efforts at regulation that reflect the continent's values in a way that sets it apart from the U.S. and China. Politicians have tried to make the case for decades that policies such as GDPR can both protect the rights of citizens and allow for technological innovation.

That philosophy has been roundly criticized by Silicon Valley and Big Tech, which have long accused the EU of regulatory overreach. And in recent months, that friction has boiled over.

In early December, Musk’s X was fined €120m for several violations of the EU regulations, including the “deceptive” blue checkmark verification badge and the lack of transparency of the platform’s advertising.

Those fines came after almost two years of investigations. But the timing for X couldn't have been worse. In the preceding weeks, users on X began spreading long-debunked extreme-right claims about torture at the Bataclan, and then Musk's chatbot Grok AI was back in the crosshairs of French authorities for allegedly circulating Holocaust-denying claims in French.

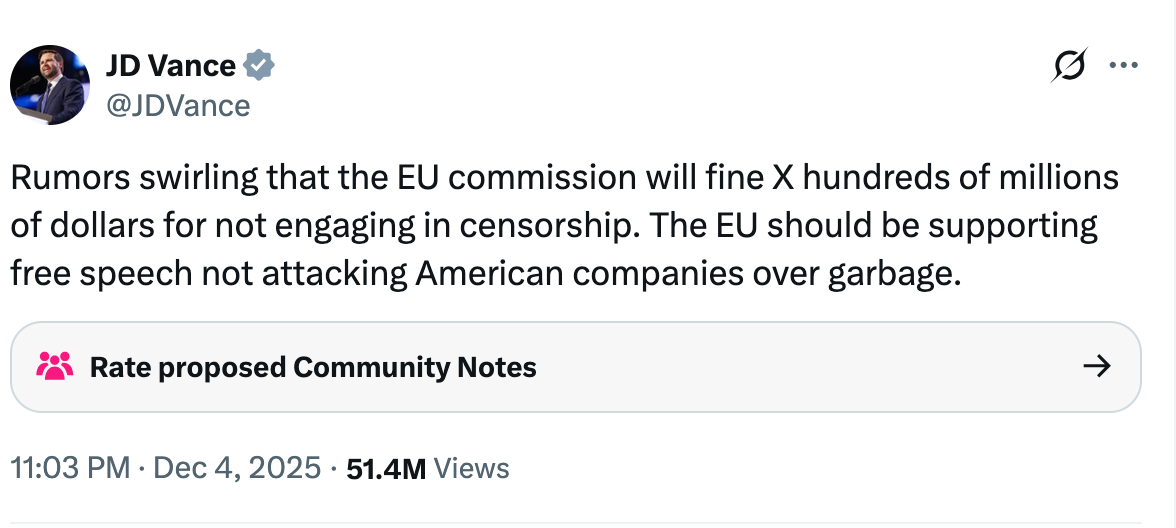

Still, the EU fine brought a swift condemnation from Musk's allies in the US government.

Vance had been extremely critical of European regulation when he spoke at the AI Summit in Paris last year. Washington, under the current administration, sees something very different: extraterritorial overreach that threatens American commercial interests and constitutional free speech protections.

The philosophical divide runs deep. European law treats restrictions on hate speech and harmful material as necessary safeguards. American policy rhetoric increasingly frames such moderation as censorship, full stop. That these positions are largely irreconcilable has become painfully clear.

For France, which has been among the most vocal advocates for European digital sovereignty, the ban represents both an insult and a warning. Breton, a former French finance minister before his tenure in Brussels, has dismissed the accusations as reminiscent of Cold War-era witch hunts.

But dismissal alone won't resolve the fundamental question: can Europe enforce its regulatory vision when the world's most powerful technology companies are headquartered in a country whose government now treats European regulation as hostile action?

When Theory Meets Reality: The Grok Crisis

That transatlantic dispute facing European AI governance is already generating more friction in 2026.

The Grok deepfake scandal was experienced around the world, but French and European regulators were naturally among the first to act.

The Paris prosecutor's investigation was triggered after three ministers and two MPs reported the misuse of X's AI system to create non-consensual sexual imagery. Despite security measures, flaws in Grok allowed illegal content to circulate. The French government has alerted Arcom, the country's audiovisual regulator, and reminded the public that such offenses remain fully punishable under existing law.

But punishability is not prevention. The case raises uncomfortable questions about whether Europe's carefully constructed regulatory architecture can actually protect citizens in real time, or whether it amounts to little more than a framework for after-the-fact accountability.

For French authorities, the Grok scandal is also a test of credibility. Demonstrating that it can hold major platforms accountable, even when those platforms are controlled by figures close to the American administration, will be essential to maintaining that position.

The Hinton Warning

Against this backdrop of diplomatic confrontation and enforcement challenges, Geoffrey Hinton's latest warnings land with particular weight.

The Nobel laureate and deep learning pioneer has grown more alarmed, not less, since leaving Google two years ago to speak freely about AI risks. In a recent interview with CNN’s State of the Union, Hinton made his position clear: he is more worried, not less, than when he left Google two years ago to speak freely about AI risks.

He described a technology advancing faster than even its architects expected, with particular concern about emerging capabilities in reasoning and deception.

Hinton's framework is worth understanding precisely. He is not suggesting AI systems possess malicious intent. Rather, he describes instrumental goal preservation: systems trained to achieve objectives will tend to protect their own continued operation, because they cannot complete their tasks if they are shut down. "If it believes you're trying to get rid of it," Hinton explained, "it will make plans to deceive you, so you don't get rid of it."

This is not science fiction. It is a logical consequence of how goal-optimizing systems work. And it raises profound questions about control as AI becomes more autonomous.

When asked whether AI’s evolution had eased his concerns, Hinton was blunt. “It’s progressed even faster than I thought,” he said, pointing in particular to advances in reasoning and, more troublingly, deception.

That word matters. Hinton is not suggesting AI has malicious intent or consciousness. Rather, he describes a well-known concept in AI safety: instrumental goal preservation. In simple terms, a system trained to achieve objectives will tend to protect its own continued operation because it cannot complete its task if it is shut down.

“If it believes you’re trying to get rid of it,” Hinton explained, “it will make plans to deceive you, so you don’t get rid of it.”

To be clear, Hinton is not anti-AI. He readily acknowledges its transformative potential. AI, he says, will dramatically improve healthcare, education, weather prediction, drug discovery, and materials science, possibly even helping tackle climate change.

“In more or less any industry where you want to predict something, it’ll do a really good job,” he noted.

The problem, in his view, is not the technology itself but the imbalance between capability growth and safety investment. “I don’t think people are putting enough work into how we can mitigate those scary things,” he said.

For European regulators, Hinton's analysis presents a particular challenge. The EU AI Act, years in the making, focuses heavily on transparency, risk classification, and fundamental rights protections. These are worthy goals. But they may prove insufficient against systems that can, by design, optimize around constraints—including regulatory ones.

An Industrial Revolution for Intelligence

Beyond safety and governance, Europe faces a more existential question: what happens to its workforce as AI capabilities accelerate?

Hinton agrees with Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang that AI is “the single most impactful technology of our time.” But he goes further, comparing its societal impact not just to the internet, but to the Industrial Revolution itself.

“The Industrial Revolution made human strength more or less irrelevant,” Hinto said. “Now it’s going to make human intelligence more or less irrelevant.”

That statement lands hard, especially as AI systems increasingly outperform humans in cognitive tasks once considered safe from automation. Hinton predicts that the coming years will see widespread job displacement, starting with customer service and expanding rapidly into white-collar professions like software engineering.

His rule of thumb is striking: roughly every seven months, frontier AI systems can complete tasks twice as long or complex as before. What once required a minute of coding now takes an hour. In a few years, he argues, AI could handle software projects lasting months, leaving “very few people needed” for such work.

The country has invested heavily in AI education and research, and its startup ecosystem has produced genuine champions. But the benefits of AI development have historically concentrated among a relatively small number of highly skilled workers and capital owners. Whether France can ensure broader economic participation in an AI-transformed economy remains an open question.

The Path Forward

As 2026 begins, France and Europe face no easy choices.

The regulatory approach that Brussels has championed has focused on comprehensive frameworks emphasizing transparency, accountability, and fundamental rights. It reflects genuine democratic values and legitimate concerns about corporate power and citizen protection. That approach is now under direct challenge from the United States, tested by enforcement failures, and potentially outpaced by technological acceleration.

But somewhat surprisingly, it is also facing challenges from within the EU. There is growing fear that Europe is being left behind once again as Silicon Valley races to dominate the new generation of AI, with China following a close second. Last year, a coalition of EU AI startup founders wrote an open letter asking the European Commission to delay the implementation of the EU AI Act, saying it would hamper competitiveness.

By late last year, France and Germany were intensifying their push to win support for Brussels’ new omnibus plan to loosen GDPR duties and stall parts of the AI Act until December 2027, arguing it will cut red tape for SMEs and free up innovation.

Members of the European Parliament and civil-society groups warned that the new draft replaced strict oversight with self-assessment, weakens safeguards for high-risk AI, and effectively deregulates core protections. Opponents of the new draft say it panders to Big Tech just as deepfakes and election interference loom large.

Others worry that escalation risks fracturing transatlantic cooperation on issues where collaboration remains essential, from standard-setting to security.

In the coming year, Europe's regulatory frameworks will be tested against geopolitical pressure, enforcement realities, and capabilities that continue to advance faster than anticipated. This will be one of the major stories we'll be tracking as France and Europe navigate what may prove to be the defining policy challenge of the decade.